Building AI That Understands Legal Documents (Not Just Reads Them)

Last updated on December 1, 2025

Reading legal documents is pattern matching. Understanding requires legal reasoning. The difference determines whether AI for legal documents creates value or liability.

Most legal document processing AI fails because it treats documents as text to parse rather than legal instruments with dependencies, hierarchies, and context that spans hundreds of pages. A limitation of liability clause on page 47 means nothing without the definitions on page 3, the exceptions in Section 12, the carve-outs in Exhibit B, and the side letter that modifies the whole framework. Systems that chunk documents into isolated segments miss these connections. Systems that try to process everything at once run out of context.

Production legal document AI requires architecture designed specifically for how legal documents actually work. This article examines core considerations for any team evaluating AI for law firms: what “understanding” means in legal AI context, why standard document processing approaches fail on legal text, the RAG architecture needed for 500-page contracts, multi-document reasoning patterns, and how production systems like Upskill AI handle this complexity.

Why Legal Documents Break Standard AI Document Processing

Legal documents have characteristics that standard document processing AI can’t handle.

Dense Text Where Every Word Carries Legal Weight

In legal documents every word exists because it modifies meaning, creates obligations, or establishes boundaries.

Consider this contract language: “Vendor shall deliver conforming goods, except as otherwise provided in Section 12 or any properly executed Change Order.” An AI legal document analysis system that treats this as simple delivery obligation misses three critical qualifiers: what “conforming” means depends on specifications elsewhere, Section 12 contains unstated exceptions, and Change Orders can override everything. Reading the sentence extracts “vendor delivers goods.” Understanding it requires knowing what modifies, qualifies, or negates that obligation across the entire document set.

Legal drafting deliberately uses precise terminology that looks similar to common language but carries specific meaning. “Reasonable,” “material,” “promptly,” and “best efforts” appear frequently. Each has case law defining boundaries, jurisdictional variations, and context-dependent interpretations. AI systems trained on general text treat these as synonyms for “sensible,” “important,” “quickly,” and “trying hard.” Legal interpretation requires understanding that “reasonable efforts” and “commercially reasonable efforts” and “best efforts” create different obligation standards with distinct case law.

Legal Language That Deviates From Training Data Patterns

A force majeure clause negotiated over 47 emails with industry-specific language, jurisdiction-particular legal concepts, and deliberately ambiguous compromises doesn’t match anything in training data. The model has no statistical pattern to follow. Without relevant training examples, the model falls back to general language understanding, missing that the specific word choices represent negotiated positions with legal implications.

Context Dependencies That Span Entire Document Sets

Standard document chunking breaks dependencies between distant sections. When a retrieval system embeds Section 15 in isolation, the embedding loses that Section 2 defines key terms, Section 8 establishes conditions precedent, Section 20 contains exceptions, and Exhibit C lists specific carve-outs. A query about Section 15 retrieves that chunk, the model generates an answer from partial information, and the response is technically accurate but legally wrong because the system missed the modifying provisions.

Cross-document references create even harder problems. Master Service Agreements reference Statement of Work documents. Contracts incorporate terms by reference without including full text. Amendments modify original agreements signed years earlier. A complete analysis requires assembling the relevant document set, understanding which provisions have been modified or superseded, and synthesizing across versions.

Ambiguity as Intentional Feature

A clause stating obligations apply “to the extent commercially reasonable” lets each party claim their interpretation when disputes arise. Such ambiguity isn’t drafting failure. Deliberate vagueness represents negotiated compromise allowing the deal to close.

AI legal document analysis systems struggle with deliberate ambiguity. They’re optimized to extract single definitive interpretations. When asked “what does this clause require?” they generate confident answers rather than flagging that the clause deliberately permits multiple readings. Production systems need to recognize when ambiguity is intentional and surface that interpretive uncertainty rather than picking one reading.

What “Understanding” Actually Means in AI Legal Document Analysis

The distinction between reading and understanding determines whether legal document processing AI creates value or liability.

Reading: Text Ingestion and Pattern Matching

AI can extract information from legal documents with high accuracy when the task involves pattern recognition. Finding all dates, dollar amounts, party names, and addresses requires parsing structured patterns. Identifying clause types (confidentiality, indemnification, limitation of liability) works when clauses follow standard formats.

Named Entity Recognition models trained on legal documents perform well at extracting structured data: contract effective dates, term lengths, payment amounts, renewal provisions, termination notice periods.

Summarization of individual sections works when the text is self-contained. An AI can read Section 7 describing payment terms and generate a coherent summary: payment due net 30, late fees of 1.5% monthly, disputes resolved through specified process. The model processes the text, identifies key points, and presents them clearly.

Classification assigns documents or clauses to predefined categories. AI model can read a contract and categorize it as “Master Services Agreement” versus “Statement of Work” versus “Amendment” with high accuracy when trained on examples.

Understanding: Contextual Reasoning Across Document Structures

Understanding requires the system to reason about relationships, implications, and interactions between provisions.

Hierarchical interpretation respects how legal documents organize information. Definitions sections establish meanings that apply throughout. General provisions get modified by specific ones. Later amendments supersede earlier terms. Cross-references create explicit dependencies. AI for legal documents must track these hierarchies and apply them correctly when reasoning about what provisions mean.

Multi-document synthesis happens constantly in legal work. Understanding the current legal relationship requires synthesizing across the document set, tracking what’s been modified, what remains in force, and which provisions apply to which aspects of the relationship.

Architecture Deep Dive: Building Legal AI That Actually Understands Documents

One of the first steps the legal AI roadmap recommends is understanding the core components of legal AI architecture to build a production-ready system.

RAG for 500-Page Contracts: Beyond Standard Chunking

Standard RAG implementations use fixed-size chunking that breaks legal documents at arbitrary boundaries. A better approach respects document structure.

Semantic section-aware chunking parses document structure before creating embeddings. Contracts have predictable organization: recitals, definitions, substantive provisions, general provisions, signature blocks. Within substantive sections, provisions have hierarchical structure with parent sections, subsections, sub-subsections. The chunking algorithm identifies these boundaries and keeps semantic units intact.

A definitions section gets chunked so each definition with its complete explanation stays together. A substantive provision with multiple subsections gets chunked at the subsection level, but each chunk includes metadata showing the parent section hierarchy. When the system later retrieves a subsection about payment terms, the metadata shows it’s part of Section 8 Payment Obligations, subsection (c) concerning late fees.

Metadata enrichment adds context to every chunk before embedding. Beyond basic document identifiers (contract name, execution date, parties), chunks carry hierarchical context (parent sections, related definitions, cross-referenced provisions). This metadata doesn’t get embedded as part of the semantic content, but it’s available during retrieval for filtering, boosting, and context assembly.

For a chunk containing “the warranty period shall be eighteen months,” metadata captures that “warranty period” is defined in Section 1.45, this provision appears in Section 7 Warranties, subsection (b), and Section 12 Limitations of Liability contains relevant exceptions. During retrieval, when this chunk ranks highly for a warranty question, the system can automatically pull the definition and related exceptions even if they didn’t match query semantics.

Graph-based cross-reference tracking builds an explicit graph of dependencies. The parsing pipeline identifies cross-references (“as defined in Section 1.3,” “subject to Section 12,” “except as provided in Exhibit B”) and creates graph edges connecting related provisions. When retrieval identifies a relevant chunk, graph traversal pulls connected nodes ensuring complete context.

The combination of section-aware chunking, metadata enrichment, and graph-based tracking handles the 500-page contract problem. Instead of trying to process the entire document at once (context limits) or fragmenting into isolated chunks (lost dependencies), the architecture processes semantically complete units while maintaining structural knowledge of how provisions connect.

Multi-Document Reasoning Patterns

Legal work routinely involves multiple related documents that must be analyzed together. Production AI legal document analysis requires architecture supporting multi-document reasoning.

Document relationship mapping establishes how documents relate before processing content. A Master Services Agreement might have three amendments, twelve Statements of Work, and two side letters. The system needs to know which documents modify which others, what the effective dates are, and which provisions apply to which relationships.

Document relationship mapping requires parsing document metadata, identifying relationships through explicit references and contextual clues, and building a document graph showing dependencies. When analyzing a current vendor relationship, the system starts with the document graph to identify the complete relevant set.

Temporal reasoning across versions tracks how terms have changed. The original MSA signed in 2018 established net 60 payment terms. Amendment 2 in 2020 changed payment terms to net 30.

Temporal reasoning requires version tracking, effective date reasoning, and supersession logic. Each document version maintains full text and metadata about what the version modifies. During retrieval, the system filters to currently effective provisions or surfaces the change history when asked about how terms have evolved.

Cross-document information synthesis combines information from multiple sources to answer questions no single document addresses. “What are our total financial obligations across all active vendor agreements?” requires finding payment provisions across a dozen contracts, understanding whether they’re one-time or recurring, checking for early termination costs, and aggregating correctly.

The architecture needs multi-document retrieval that pulls relevant chunks from across the document set, synthesis agents that combine information while tracking source attribution, and validation that ensures the synthesized answer accurately represents the source materials.

Category-Aware Retrieval for Legal Documents

Different types of legal questions require different retrieval strategies. Production systems adapt retrieval based on query category.

Definitional queries (“What is the definition of Confidential Information?”) need exact matches, not semantic similarity. The system should retrieve the actual definition section, not conceptually similar text discussing confidential information. Implementation uses hybrid search weighted heavily toward keyword matching for queries containing “define,” “definition,” “means,” or question patterns asking what specific capitalized terms mean.

Obligation queries (“What are the vendor’s indemnification obligations?”) require finding all relevant provisions including main clauses, exceptions, limitations, and conditions. Obligation queries need semantic search to find various ways obligations might be expressed, combined with structural awareness to retrieve related exceptions and qualifications.

The retrieval strategy starts with semantic search for indemnification language, identifies all matching sections and subsections, uses graph traversal to find exceptions and carve-outs, and assembles complete obligation framework including conditions, limitations, and relevant definitions.

Scenario analysis queries (“What happens if we terminate early?”) require reasoning about multiple provisions. Early termination might trigger termination notice requirements, early termination fees, return of confidential information obligations, survival of certain provisions, and final payment calculations. No single section contains the complete answer.

The system handles this through multi-hop retrieval: initial search for termination provisions, identification of cross-referenced sections (payment, confidentiality, survival), assembly of all relevant provisions, and synthesis showing how they interact for the specific scenario.

Risk identification queries (“What are the biggest risks in this contract?”) need different logic. Instead of retrieving based on query similarity, the system applies learned patterns about problematic provisions: unlimited liability, one-sided termination rights, unreasonable indemnification burdens, missing limitation of liability clauses, problematic intellectual property provisions.

Risk identification combines rule-based risk detection, AI and LLM models trained on risk-annotated contracts, and comparative analysis against standard templates or past negotiations. The risk detection system flags provisions that deviate significantly from norms and explains why those provisions create risk.

Get the complete AI Launch Plan covering production readiness requirements for legal AI systems.

Case Study: AI Legal Document Analysis in Production

Softcery built Upskill AI for The Compliance Company, a leading consultancy across New Zealand and Australia. The challenge was converting deep compliance expertise into a scalable AI system that maintains the accuracy standards the domain demands.

Answer Quality Controls: Multiple Validation Layers

The system implements three validation mechanisms that run before answers reach users.

Relevance filtering detects questions outside the system’s knowledge domain. When compliance professionals ask about topics not covered in the documentation, the system explicitly states the knowledge base doesn’t contain that information rather than attempting to answer from tangentially related materials. Relevance filtering prevents the dangerous failure mode where AI generates plausible-sounding responses without actual knowledge.

Context-aware query rewriting handles follow-up questions in conversation. Consider a compliance professional who first asks “What are the licensing requirements for real estate managers?” and then follows up with “What about independent contractors?” Without context awareness, the system would search for “independent contractors” in isolation and return irrelevant results. With context-aware rewriting, the system reformulates the follow-up to “What are the licensing requirements for independent contractors?” maintaining the conversation thread and finding the right regulatory information.

Validation layer checks three dimensions before displaying answers:

- correctness (is the answer consistent with retrieved context, without contradictions or hallucinations?);

- relevance (does the response directly answer the user’s question completely and usefully without straying off-topic?);

- retrieval relevance (do the retrieved documents actually match the query topic and contain applicable regulatory requirements?). Responses failing validation get regenerated with stricter instructions or flagged for expert review.

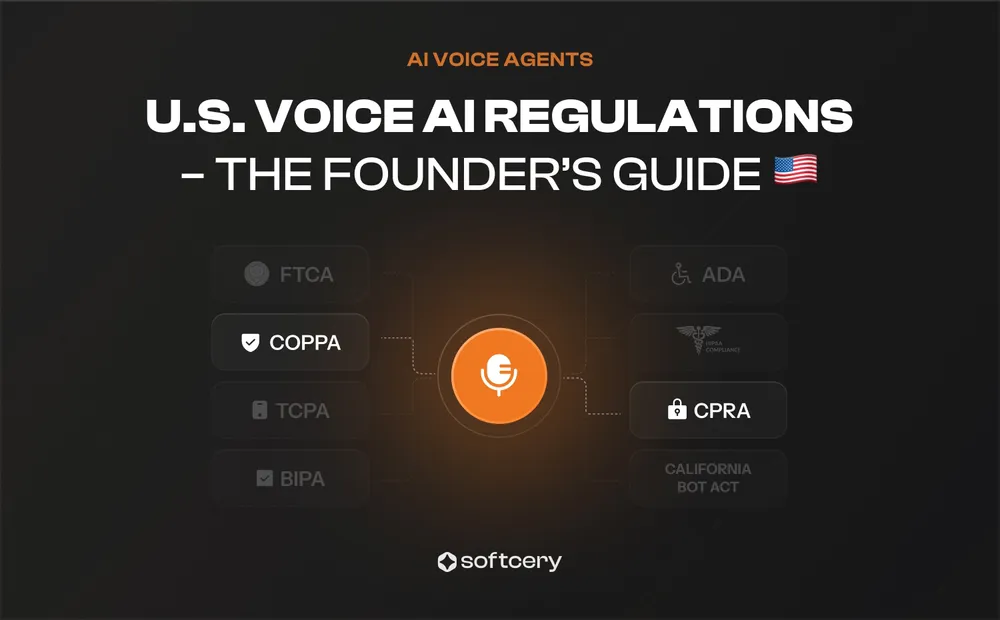

Multi-Jurisdiction Support: Infrastructure-Level Separation

The system maintains separate knowledge bases for New Zealand and Australian regulatory frameworks. Architectural separation at infrastructure level prevents cross-jurisdiction contamination that filtering approaches can’t guarantee.

New Zealand compliance queries route exclusively to the NZ knowledge base. Australian queries route to the AU knowledge base. Infrastructure-level separation ensures semantic search doesn’t accidentally surface Australian regulations for New Zealand questions or vice versa.

Category-Aware Retrieval: Prioritizing Authoritative Sources

Different document types carry different authority levels. Acts (statutes) carry more weight than guidance documents explaining how agencies interpret regulations.

The retrieval system implements category-aware ranking that prioritizes Acts over guidance documents when both match query semantics. Category-aware ranking ensures compliance professionals get authoritative sources first while making interpretive guidance available for additional context. The category metadata gets attached during document processing and influences retrieval scoring. During response generation, the prompt instructions also enforce this document hierarchy, ensuring the AI weights statutory requirements above interpretive guidance when synthesizing answers.

Evidence-Backed Responses: Inline Citations with Source Links

Every answer includes inline citations linking claims to source documents. When the system states a compliance requirement, the citation isn’t just text but a direct link to the specific document section containing that requirement.

Inline citations enable immediate verification. Compliance professionals can click through to source materials to confirm the AI’s interpretation, review additional context, or extract specific regulatory language for client communications. The evidence-backed approach with traceable sources addresses the accuracy requirements inherent to compliance work.

For technical guidance on legal AI implementation, reach out at [email protected] or book a call.

Conclusion

AI legal systems that read text perform well on extraction tasks: finding dates, amounts, party names, clause types. These capabilities matter for document organization and basic information retrieval. Systems that understand legal context handle the questions that actually matter: how do these provisions interact? What happens in this scenario? Where are the risks? How have terms changed across versions?

Building AI that understands legal documents requires architecture designed for legal document structure. Section-aware chunking respects how legal provisions organize information. Metadata enrichment maintains hierarchical context. Graph-based cross-reference tracking preserves dependencies across distant sections. Multi-document reasoning synthesizes across related agreements. Category-aware retrieval adapts strategy based on question type.

Legal document AI that works in production requires systematic engineering treating verification and context preservation as core requirements rather than optional enhancements.

Frequently Asked Questions

Reading means extracting text, identifying patterns like dates and amounts, classifying clause types, and summarizing individual sections. Understanding means reasoning about relationships across hundreds of pages, connecting provisions to definitions, tracking exceptions and carve-outs, synthesizing information from multiple related documents, and recognizing when ambiguity is intentional. AI can read with high accuracy using standard NLP techniques. Understanding requires specialized architecture preserving legal document structure, hierarchical context, and cross-reference dependencies.

Standard approaches use fixed-size chunking that breaks legal documents at arbitrary boundaries, destroying semantic units. A limitation of liability clause depends on definitions elsewhere, exceptions in other sections, and carve-outs in exhibits. Fixed chunking isolates these related provisions, causing AI to miss critical context. Legal documents also use precise terminology with case law-defined meanings that differ from general language. “Reasonable efforts” versus “best efforts” creates different obligation standards, but general-purpose language models treat them as synonyms. Specialized legal document processing requires section-aware chunking, metadata enrichment with hierarchical context, and graph-based tracking of cross-references.

Production RAG for legal documents uses semantic section-aware chunking that preserves complete provisions instead of arbitrary splits, metadata enrichment adding hierarchical context (parent sections, related definitions, cross-references) to every chunk, and graph-based dependency tracking building explicit links between related provisions. When retrieval identifies a relevant section, the system uses graph traversal to automatically pull connected definitions, exceptions, and carve-outs. Graph traversal provides complete legal context without processing the entire 500-page document at once (context limits) or fragmenting into isolated chunks (lost dependencies). The architecture processes semantically complete units while maintaining structural knowledge of how provisions connect.

Multi-document reasoning requires document relationship mapping to understand how agreements modify each other, temporal reasoning tracking which provisions are currently effective across amendments, and cross-document synthesis combining information from multiple sources. Multi-document systems maintain document graphs showing dependencies (Master Service Agreement, amendments, Statements of Work, side letters), version tracking with effective dates and supersession logic, and multi-document retrieval that pulls relevant chunks from across the set while maintaining source attribution. Each synthesized claim links to the specific source document enabling verification.

Effective legal AI systems combine several architectural elements:

- infrastructure-level separation for different jurisdictions or document categories to prevent contamination;

- relevance filtering that explicitly acknowledges when queries fall outside the system’s knowledge domain rather than generating plausible-sounding nonsense;

- context-aware query handling that maintains conversation threads for follow-up questions;

- category-aware retrieval that prioritizes authoritative sources (statutes over guidance documents);

- multi-layer validation checking correctness, relevance, and retrieval quality before displaying answers;

- inline citations linking every claim to source documents for immediate verification.

Focus on the 20% that actually moves the needle. Your custom launch plan shows you exactly which work gets you to launch and which work is just perfectionism – so you can stop gold-plating and start shipping.

Get Your AI Launch Plan